Working with RabbitMQ exchanges and publishing messages from Ruby with Bunny

About this guide

This guide covers the use of exchanges according to the AMQP 0.9.1 specification, including broader topics related to message publishing, common usage scenarios and how to accomplish typical operations using Bunny.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License (including images and stylesheets). The source is available on Github.

What version of Bunny does this guide cover?

This guide covers Bunny 2.10.x and later versions.

Exchanges in AMQP 0.9.1 — Overview

What are AMQP exchanges?

An exchange accepts messages from a producer application and routes them to message queues. They can be thought of as the "mailboxes" of the AMQP world. Unlike some other messaging middleware products and protocols, in AMQP, messages are not published directly to queues. Messages are published to exchanges that route them to queue(s) using pre-arranged criteria called bindings.

There are multiple exchange types in the AMQP 0.9.1 specification, each with its own routing semantics. Custom exchange types can be created to deal with sophisticated routing scenarios (e.g. routing based on geolocation data or edge cases) or just for convenience.

Concept of Bindings

A binding is an association between a queue and an exchange. A queue must be bound to at least one exchange in order to receive messages from publishers. Learn more about bindings in the Bindings guide.

Exchange attributes

Exchanges have several attributes associated with them:

- Name

- Type (direct, fanout, topic, headers or some custom type)

- Durability

- Whether the exchange is auto-deleted when no longer used

- Other metadata (sometimes known as X-arguments)

Exchange types

There are four built-in exchange types in AMQP v0.9.1:

- Direct

- Fanout

- Topic

- Headers

As stated previously, each exchange type has its own routing semantics and new exchange types can be added by extending brokers with plugins. Custom exchange types begin with "x-", much like custom HTTP headers, e.g. x-consistent-hash exchange or x-random exchange.

Message attributes

Before we start looking at various exchange types and their routing semantics, we need to introduce message attributes. Every AMQP message has a number of attributes. Some attributes are important and used very often, others are rarely used. AMQP message attributes are metadata and are similar in purpose to HTTP request and response headers.

Every AMQP 0.9.1 message has an attribute called routing key. The routing key is an "address" that the exchange may use to decide how to route the message. This is similar to, but more generic than, a URL in HTTP. Most exchange types use the routing key to implement routing logic, but some ignore it and use other criteria (e.g. message content).

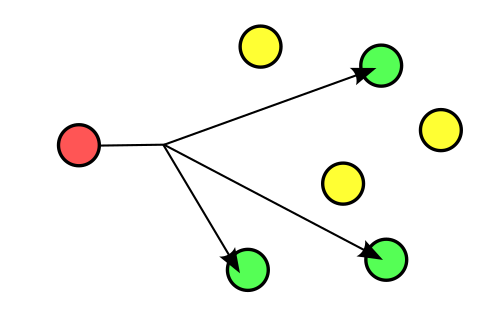

Fanout exchanges

How fanout exchanges route messages

A fanout exchange routes messages to all of the queues that are bound to it and the routing key is ignored. If N queues are bound to a fanout exchange, when a new message is published to that exchange a copy of the message is delivered to all N queues. Fanout exchanges are ideal for the broadcast routing of messages.

Graphically this can be represented as:

Declaring a fanout exchange

There are two ways to declare a fanout exchange:

- Using the

Bunny::Channel#fanoutmethod - Instantiate

Bunny::Exchangedirectly

Here are two examples to demonstrate:

require "bunny"

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = ch.fanout("activity.events")

require "bunny"

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = Bunny::Exchange.new(ch, :fanout, "activity.events")

Fanout routing example

To demonstrate fanout routing behavior we can declare ten server-named exclusive queues, bind them all to one fanout exchange and then publish a message to the exchange:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

# encoding: utf-8

require "rubygems"

require "bunny"

puts "=> Fanout exchange routing"

puts

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = ch.fanout("examples.pings")

10.times do |i|

q = ch.queue("", :auto_delete => true).bind(x)

q.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "[consumer] #{q.name} received a message: #{payload}"

end

end

x.publish("Ping")

sleep 0.5

x.delete

puts "Disconnecting..."

conn.close

When run, this example produces the following output:

=> Fanout exchange routing [consumer] amq.gen-A8z-tj-n_0U39GdPGncV-A received a message: Ping [consumer] amq.gen-jht-OtRwdD8LuHMxrA5SNQ received a message: Ping [consumer] amq.gen-LQTh8IdojOCrvOnEuFog8w received a message: Ping [consumer] amq.gen-PV-Dg8_gSvLO9eK6le6wwQ received a message: Ping [consumer] amq.gen-ofAMc3FXRZIj3O55fXDSwA received a message: Ping [consumer] amq.gen-TXJiZEjwZ0squ12_Z9mP0A received a message: Ping [consumer] amq.gen-XQjh2xrC9khbMZMg_0Zzfw received a message: Ping [consumer] amq.gen-XVSKsdWwhyxRiJn-jAFEGg received a message: Ping [consumer] amq.gen-ZaY2pD_9NaOICxAMWPoIYw received a message: Ping [consumer] amq.gen-oElfvP_crgASWkk6EhrJLA received a message: Ping Disconnecting...

Each of the queues bound to the exchange receives a copy of the message.

Fanout use cases

Because a fanout exchange delivers a copy of a message to every queue bound to it, its use cases are quite similar:

- Massively multiplayer online (MMO) games can use it for leaderboard updates or other global events

- Sport news sites can use fanout exchanges for distributing score updates to mobile clients in near real-time

- Distributed systems can broadcast various state and configuration updates

- Group chats can distribute messages between participants using a fanout exchange (although AMQP does not have a built-in concept of presence, so XMPP may be a better choice)

Pre-declared fanout exchanges

AMQP 0.9.1 brokers must implement a fanout exchange type and

pre-declare one instance with the name of "amq.fanout".

Applications can rely on that exchange always being available to them. Each vhost has a separate instance of that exchange, it is not shared across vhosts for obvious reasons.

Direct exchanges

How direct exchanges route messages

A direct exchange delivers messages to queues based on a message routing key, an attribute that every AMQP v0.9.1 message contains.

Here is how it works:

- A queue binds to the exchange with a routing key K

- When a new message with routing key R arrives at the direct exchange, the exchange routes it to the queue if K = R

A direct exchange is ideal for the unicast routing of messages (although they can be used for multicast routing as well).

Here is a graphical representation:

Declaring a direct exchange

- Using the

Bunny::Channel#directmethod - Instantiate

Bunny::Exchangedirectly

Here are two examples to demonstrate:

require "bunny"

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = ch.direct("imaging")

require "bunny"

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = Bunny::Exchange.new(ch, :direct, "imaging")

Direct routing example

Since direct exchanges use the message routing key for routing, message producers need to specify it:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

# encoding: utf-8

require "rubygems"

require "bunny"

puts "=> Direct exchange routing"

puts

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = ch.direct("examples.imaging")

q1 = ch.queue("", :auto_delete => true).bind(x, :routing_key => "resize")

q1.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "[consumer] #{q1.name} received a 'resize' message"

end

q2 = ch.queue("", :auto_delete => true).bind(x, :routing_key => "watermark")

q2.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "[consumer] #{q2.name} received a 'watermark' message"

end

# just an example

data = rand.to_s

x.publish(data, :routing_key => "resize")

x.publish(data, :routing_key => "watermark")

sleep 0.5

x.delete

q1.delete

q2.delete

puts "Disconnecting..."

conn.close

The routing key will then be compared for equality with routing keys on bindings, and consumers that subscribed with the same routing key each get a copy of the message.

Output for the example looks like this:

=> Direct exchange routing

[consumer] amq.gen-8XIeaBCmykwnJUtHVEkT5Q received a 'resize' message

[consumer] amq.gen-Zht5YW3_MhK-YBLZouxp5Q received a 'watermark' message

Disconnecting...

Direct Exchanges and Load Balancing of Messages

Direct exchanges are often used to distribute tasks between multiple workers (instances of the same application) in a round robin manner. When doing so, it is important to understand that, in AMQP 0.9.1, messages are load balanced between consumers and not between queues.

The Queues and Consumers guide provides more information on this subject.

Pre-declared direct exchanges

AMQP 0.9.1 brokers must implement a direct exchange type and pre-declare two instances:

amq.direct- "" exchange known as default exchange (unnamed, referred to as an empty string by many clients including Bunny)

Applications can rely on those exchanges always being available to them. Each vhost has separate instances of those exchanges, they are not shared across vhosts for obvious reasons.

Default exchange

The default exchange is a direct exchange with no name (Bunny refers to it using an empty string) pre-declared by the broker. It has one special property that makes it very useful for simple applications, namely that every queue is automatically bound to it with a routing key which is the same as the queue name.

For example, when you declare a queue with the name of "search.indexing.online", RabbitMQ will bind it to the default exchange using "search.indexing.online" as the routing key. Therefore a message published to the default exchange with routing key = "search.indexing.online" will be routed to the queue "search.indexing.online". In other words, the default exchange makes it seem like it is possible to deliver messages directly to queues, even though that is not technically what is happening.

The default exchange is used by the "Hello, World" example:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

# encoding: utf-8

require "rubygems"

require "bunny"

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

q = ch.queue("bunny.examples.hello_world", :auto_delete => true)

q.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "Received #{payload}"

end

q.publish("Hello!", :routing_key => q.name)

sleep 1.0

conn.close

Direct Exchange Use Cases

Direct exchanges can be used in a wide variety of cases:

- Direct (near real-time) messages to individual players in an MMO game

- Delivering notifications to specific geographic locations (for example, points of sale)

- Distributing tasks between multiple instances of the same application all having the same function, for example, image processors

- Passing data between workflow steps, each having an identifier (also consider using headers exchange)

- Delivering notifications to individual software services in the network

Topic Exchanges

How Topic Exchanges Route Messages

Topic exchanges route messages to one or many queues based on matching between a message routing key and the pattern that was used to bind a queue to an exchange. The topic exchange type is often used to implement various publish/subscribe pattern variations.

Topic exchanges are commonly used for the multicast routing of messages.

Topic exchanges can be used for broadcast routing, but fanout exchanges are usually more efficient for this use case.

Topic Exchange Routing Example

Two classic examples of topic-based routing are stock price updates

and location-specific data (for instance, weather

broadcasts). Consumers indicate which topics they are interested in

(think of it like subscribing to a feed for an individual tag of your

favourite blog as opposed to the full feed). The routing is enabled by

specifying a routing pattern to the Bunny::Queue#bind method, for

example:

x = ch.topic("weathr", :auto_delete => true)

q = ch.queue("americas.south", :auto_delete => true).bind(x, :routing_key => "americas.south.#")

q.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "An update for South America: #{payload}, routing key is #{delivery_info.routing_key}"

end

In the example above we bind a queue with the name of "americas.south" to the topic exchange declared earlier using the Bunny::Queue#bind method. This means that

only messages with a routing key matching "americas.south.#" will be routed to the "americas.south" queue.

A routing pattern consists of several words separated by dots, in a similar way to URI path segments being joined by slash. A few of examples:

- asia.southeast.thailand.bangkok

- sports.basketball

- usa.nasdaq.aapl

- tasks.search.indexing.accounts

The following routing keys match the "americas.south.#" pattern:

- americas.south

- americas.south.brazil

- americas.south.brazil.saopaolo

- americas.south.chile.santiago

In other words, the "#" part of the pattern matches 0 or more words.

For the pattern "americas.south.*", some matching routing keys are:

- americas.south.brazil

- americas.south.chile

- americas.south.peru

but not

- americas.south

- americas.south.chile.santiago

As you can see, the "*" part of the pattern matches 1 word only.

Full example:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

# encoding: utf-8

require "rubygems"

require "bunny"

connection = Bunny.new

connection.start

channel = connection.create_channel

# topic exchange name can be any string

exchange = channel.topic("weathr", :auto_delete => true)

# Subscribers.

channel.queue("americas.north").bind(exchange, :routing_key => "americas.north.#").subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "An update for North America: #{payload}, routing key is #{delivery_info.routing_key}"

end

channel.queue("americas.south").bind(exchange, :routing_key => "americas.south.#").subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "An update for South America: #{payload}, routing key is #{delivery_info.routing_key}"

end

channel.queue("us.california").bind(exchange, :routing_key => "americas.north.us.ca.*").subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "An update for US/California: #{payload}, routing key is #{delivery_info.routing_key}"

end

channel.queue("us.tx.austin").bind(exchange, :routing_key => "#.tx.austin").subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "An update for Austin, TX: #{payload}, routing key is #{delivery_info.routing_key}"

end

channel.queue("it.rome").bind(exchange, :routing_key => "europe.italy.rome").subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "An update for Rome, Italy: #{payload}, routing key is #{delivery_info.routing_key}"

end

channel.queue("asia.hk").bind(exchange, :routing_key => "asia.southeast.hk.#").subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, payload|

puts "An update for Hong Kong: #{payload}, routing key is #{delivery_info.routing_key}"

end

exchange.publish("San Diego update", :routing_key => "americas.north.us.ca.sandiego").

publish("Berkeley update", :routing_key => "americas.north.us.ca.berkeley").

publish("San Francisco update", :routing_key => "americas.north.us.ca.sanfrancisco").

publish("New York update", :routing_key => "americas.north.us.ny.newyork").

publish("São Paolo update", :routing_key => "americas.south.brazil.saopaolo").

publish("Hong Kong update", :routing_key => "asia.southeast.hk.hongkong").

publish("Kyoto update", :routing_key => "asia.southeast.japan.kyoto").

publish("Shanghai update", :routing_key => "asia.southeast.prc.shanghai").

publish("Rome update", :routing_key => "europe.italy.roma").

publish("Paris update", :routing_key => "europe.france.paris")

sleep 1.0

connection.close

Topic Exchange Use Cases

Topic exchanges have a very broad set of use cases. Whenever a problem involves multiple consumers/applications that selectively choose which type of messages they want to receive, the use of topic exchanges should be considered. To name a few examples:

- Distributing data relevant to specific geographic location, for example, points of sale

- Background task processing done by multiple workers, each capable of handling specific set of tasks

- Stocks price updates (and updates on other kinds of financial data)

- News updates that involve categorization or tagging (for example, only for a particular sport or team)

- Orchestration of services of different kinds in the cloud

- Distributed architecture/OS-specific software builds or packaging where each builder can handle only one architecture or OS

Declaring/Instantiating Exchanges

With Bunny, exchanges can be declared in two ways: by instantiating

Bunny::Exchange or by using a number of convenience methods on

Bunny::Channel:

Bunny::Channel#default_exchangeBunny::Channel#directBunny::Channel#topicBunny::Channel#fanoutBunny::Channel#headers

The previous sections on specific exchange types (direct, fanout, headers, etc.) provide plenty of examples of how these methods can be used.

Checking of an Exchange Exists

Sometimes it's convenient to check if an exchange exists. To do so, at the protocol

level you use exchange.declare with passive seto to true. In response

RabbitMQ responds with a channel exception if the exchange does not exist.

Bunny provides a convenience method, Bunny::Session#exchange_exists?, to do this:

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

conn.exchange_exists?("logs")

Publishing messages

To publish a message to an exchange, use Bunny::Exchange#publish:

x.publish("some data")

The method accepts message body and a number of message and delivery metadata options. Routing key can be blank ("") but never nil.

The body needs to be a string. The message payload is completely opaque to the library and is not modified by Bunny or RabbitMQ in any way.

Data serialization

You are encouraged to take care of data serialization before publishing (i.e. by using JSON, Thrift, Protocol Buffers or some other serialization library). Note that because AMQP is a binary protocol, text formats like JSON largely lose their advantage of being easy to inspect as data travels across the network, so if bandwidth efficiency is important, consider using MessagePack or Protocol Buffers.

A few popular options for data serialization are:

- JSON: json gem (part of standard Ruby library on Ruby 1.9) or yajl-ruby (Ruby bindings to YAJL)

- BSON: bson gem for JRuby (implemented as a Java extension) or bson_ext for C-based Rubies

- Message Pack has Ruby bindings and provides a Java implementation for JRuby

- XML: Nokogiri is a swiss army knife for XML processing with Ruby, built on top of libxml2

- Protocol Buffers: beefcake

Message metadata

RabbitMQ messages have various metadata attributes that can be set

when a message is published. Some of the attributes are well-known and

mentioned in the AMQP 0.9.1 specification, others are specific to a

particular application. Well-known attributes are listed here as

options that Bunny::Exchange#publish takes:

:persistent:mandatory:timestamp:expiration:type:reply_to:content_type:content_encoding:correlation_id:priority:message_id:user_id:app_id

All other attributes can be added to a headers table (in Ruby, a

hash) that Bunny::Exchange#publish accepts as the :headers option.

An example:

now = Time.now

x.publish("hello",

:routing_key => queue_name,

:app_id => "bunny.example",

:priority => 8,

:type => "kinda.checkin",

# headers table keys can be anything

:headers => {

:coordinates => {

:latitude => 59.35,

:longitude => 18.066667

},

:time => now,

:participants => 11,

:venue => "Stockholm",

:true_field => true,

:false_field => false,

:nil_field => nil,

:ary_field => ["one", 2.0, 3, [{"abc" => 123}]]

},

:timestamp => now.to_i,

:reply_to => "a.sender",

:correlation_id => "r-1",

:message_id => "m-1")

- :routing_key

- Used for routing messages depending on the exchange type and configuration.

- :persistent

- When set to true, RabbitMQ will persist message to disk.

- :mandatory

- This flag tells the server how to react if the message cannot be routed to a queue. If this flag is set to true, the server will return an unroutable message to the producer with a `basic.return` AMQP method. If this flag is set to false, the server silently drops the message.

- :content_type

- MIME content type of message payload. Has the same purpose/semantics as HTTP Content-Type header.

- :content_encoding

- MIME content encoding of message payload. Has the same purpose/semantics as HTTP Content-Encoding header.

- :priority

- Message priority, from 0 to 9.

- :message_id

- Message identifier as a string. If applications need to identify messages, it is recommended that they use this attribute instead of putting it into the message payload.

- :reply_to

- Commonly used to name a reply queue (or any other identifier that helps a consumer application to direct its response). Applications are encouraged to use this attribute instead of putting this information into the message payload.

- :correlation_id

- ID of the message that this message is a reply to. Applications are encouraged to use this attribute instead of putting this information into the message payload.

- :type

- Message type as a string. Recommended to be used by applications instead of including this information into the message payload.

- :user_id

- Sender's identifier. Note that RabbitMQ will check that the value of this attribute is the same as username AMQP connection was authenticated with, it SHOULD NOT be used to transfer, for example, other application user ids or be used as a basis for some kind of Single Sign-On solution.

- :app_id

- Application identifier string, for example, "eventoverse" or "webcrawler"

- :timestamp

- Timestamp of the moment when message was sent, in seconds since the Epoch

- :expiration

- Message expiration specification as a string

- :arguments

- A map of any additional attributes that the application needs. Nested hashes are supported. Keys must be strings.

It is recommended that application authors use well-known message attributes when applicable instead of relying on custom headers or placing information in the message body. For example, if your application messages have priority, publishing timestamp, type and content type, you should use the respective AMQP message attributes instead of reinventing the wheel.

Validated User ID

In some scenarios it is useful for consumers to be able to know the identity of the user who published a message. RabbitMQ implements a feature known as validated User ID. If this property is set by a publisher, its value must be the same as the name of the user used to open the connection. If the user-id property is not set, the publisher's identity is not validated and remains private.

Publishing Callbacks and Reliable Delivery in Distributed Environments

A commonly asked question about RabbitMQ clients is "how to execute a piece of code after a message is received".

Message publishing with Bunny happens in several steps:

Bunny::Exchange#publishtakes a payload and various metadata attributes- Resulting payload is staged for writing

- On the next event loop tick, data is transferred to the OS kernel using one of the underlying NIO APIs

- OS kernel buffers data before sending it

- Network driver may also employ buffering

In cases when you cannot afford to lose a single message, AMQP 0.9.1 applications can use one (or a combination of) the following protocol features:

- Publisher confirms (a RabbitMQ-specific extension to AMQP 0.9.1)

- Publishing messages as mandatory

- Transactions (these introduce noticeable overhead and have a relatively narrow set of use cases)

A more detailed overview of the pros and cons of each option can be found in a blog post that introduces Publisher Confirms extension by the RabbitMQ team. The next sections of this guide will describe how the features above can be used with Bunny.

Publishing messages as mandatory

When publishing messages, it is possible to use the :mandatory

option to publish a message as "mandatory". When a mandatory message

cannot be routed to any queue (for example, there are no bindings or

none of the bindings match), the message is returned to the producer.

The following code example demonstrates a message that is published as mandatory but cannot be routed (no bindings) and thus is returned back to the producer:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

# encoding: utf-8

require "rubygems"

require "bunny"

puts "=> Publishing messages as mandatory"

puts

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = ch.default_exchange

x.on_return do |return_info, properties, content|

puts "Got a returned message: #{content}"

end

q = ch.queue("", :exclusive => true)

q.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, content|

puts "Consumed a message: #{content}"

end

x.publish("This will NOT be returned", :mandatory => true, :routing_key => q.name)

x.publish("This will be returned", :mandatory => true, :routing_key => "akjhdfkjsh#{rand}")

sleep 0.5

puts "Disconnecting..."

conn.close

Returned messages

When a message is returned, the application that produced it can handle that message in different ways:

- Store it for later redelivery in a persistent store

- Publish it to a different destination

- Log the event and discard the message

Returned messages contain information about the exchange they were

published to. Bunny associates returned message callbacks with

consumers. To handle returned messages, use

Bunny::Exchange#on_return:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

# encoding: utf-8

require "rubygems"

require "bunny"

puts "=> Publishing messages as mandatory"

puts

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = ch.default_exchange

x.on_return do |return_info, properties, content|

puts "Got a returned message: #{content}"

end

q = ch.queue("", :exclusive => true)

q.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, content|

puts "Consumed a message: #{content}"

end

x.publish("This will NOT be returned", :mandatory => true, :routing_key => q.name)

x.publish("This will be returned", :mandatory => true, :routing_key => "akjhdfkjsh#{rand}")

sleep 0.5

puts "Disconnecting..."

conn.close

A returned message handler has access to AMQP method (basic.return)

information, message metadata and payload (as a byte array). The

metadata and message body are returned without modifications so that

the application can store the message for later redelivery.

Publishing Persistent Messages

Messages potentially spend some time in the queues to which they were routed before they are consumed. During this period of time, the broker may crash or experience a restart. To survive it, messages must be persisted to disk. This has a negative effect on performance, especially with network attached storage like NAS devices and Amazon EBS. AMQP 0.9.1 lets applications trade off performance for durability, or vice versa, on a message-by-message basis.

To publish a persistent message, use the :persistent option that

Bunny::Exchange#publish accepts:

x.publish(data, :persistent => true)

Note that in order to survive a broker crash, the messages MUST be persistent and the queue that they were routed to MUST be durable.

Durability and Message Persistence provides more information on the subject.

Message Priority

Starting with RabbitMQ 3.5, queues can be instructed to support message priorities.

To specify a priority on a message, pass the :priority key to

Bunny::Exchange#publish. Note that priority queues have certain

limitations listed in the RabbitMQ documentation.

Publishing In Multi-threaded Environments

In other words, publishers in your application that publish from separate threads should use their own channels. The same is a good idea for consumers.

Headers exchanges

Now that message attributes and publishing have been introduced, it is time to take a look at one more core exchange type in AMQP 0.9.1. It is called the headers exchange type and is quite powerful.

How headers exchanges route messages

An Example Problem Definition

The best way to explain headers-based routing is with an example. Imagine a distributed continuous integration system that distributes builds across multiple machines with different hardware architectures (x86, IA-64, AMD64, ARM family and so on) and operating systems. It strives to provide a way for a community to contribute machines to run tests on and a nice build matrix like the one WebKit uses. One key problem such systems face is build distribution. It would be nice if a messaging broker could figure out which machine has which OS, architecture or combination of the two and route build request messages accordingly.

A headers exchange is designed to help in situations like this by routing on multiple attributes that are more easily expressed as message metadata attributes (headers) rather than a routing key string.

Routing on Multiple Message Attributes

Headers exchanges route messages based on message header

matching. Headers exchanges ignore the routing key attribute. Instead,

the attributes used for routing are taken from the "headers"

attribute. When a queue is bound to a headers exchange, the

:arguments attribute is used to define matching rules:

q = ch.queue("hosts.ip-172-37-11-56")

x = ch.headers("requests")

q.bind(x, :arguments => {"os" => "linux"})

When matching on one header, a message is considered matching if the value of the header equals the value specified upon binding. An example that demonstrates headers routing:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

# encoding: utf-8

require "rubygems"

require "bunny"

puts "=> Headers exchange routing"

puts

conn = Bunny.new

conn.start

ch = conn.create_channel

x = ch.headers("headers")

q1 = ch.queue("", :exclusive => true).bind(x, :arguments => {"os" => "linux", "cores" => 8, "x-match" => "all"})

q2 = ch.queue("", :exclusive => true).bind(x, :arguments => {"os" => "osx", "cores" => 4, "x-match" => "any"})

q1.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, content|

puts "#{q1.name} received #{content}"

end

q2.subscribe do |delivery_info, properties, content|

puts "#{q2.name} received #{content}"

end

x.publish("8 cores/Linux", :headers => {"os" => "linux", "cores" => 8})

x.publish("8 cores/OS X", :headers => {"os" => "osx", "cores" => 8})

x.publish("4 cores/Linux", :headers => {"os" => "linux", "cores" => 4})

sleep 0.5

conn.close

When executed, it outputs

=> Headers exchange routing

amq.gen-xhIzykDAjfcC4orMsi0O6Q received 8 cores/Linux

amq.gen-6O1oKjVd8QbKr7zyy7ssbg received 8 cores/OS X

amq.gen-6O1oKjVd8QbKr7zyy7ssbg received 4 cores/Linux

Matching All vs Matching One

It is possible to bind a queue to a headers exchange using more than one header for matching. In this case, the broker needs one more piece of information from the application developer, namely, should it consider messages with any of the headers matching, or all of them? This is what the "x-match" binding argument is for.

When the "x-match" argument is set to "any", just one matching

header value is sufficient. So in the example above, any message with

a "cores" header value equal to 8 will be considered matching.

Declaring a Headers Exchange

There are two ways to declare a headers exchange, either instantiate

Bunny::Exchange directly:

x = Bunny::Exchange.new(ch, :headers, "matching")

Or use the Bunny::Channel#headers method:

x = ch.headers("matching")

Headers Exchange Routing

When there is just one queue bound to a headers exchange, messages are

routed to it if any or all of the message headers match those

specified upon binding. Whether it is "any header" or "all of them"

depends on the "x-match" header value. In the case of multiple

queues, a headers exchange will deliver a copy of a message to each

queue, just like direct exchanges do. Distribution rules between

consumers on a particular queue are the same as for a direct exchange.

Headers Exchange Use Cases

Headers exchanges can be looked upon as "direct exchanges on steroids" and because they route based on header values, they can be used as direct exchanges where the routing key does not have to be a string; it could be an integer or a hash (dictionary) for example.

Some specific use cases:

- Transfer of work between stages in a multi-step workflow (routing slip pattern)

- Distributed build/continuous integration systems can distribute builds based on multiple parameters (OS, CPU architecture, availability of a particular package).

Pre-declared Headers Exchanges

RabbitMQ implements a headers exchange type and pre-declares one

instance with the name of "amq.match". RabbitMQ also pre-declares

one instance with the name of "amq.headers". Applications can rely

on those exchanges always being available to them. Each vhost has a

separate instance of those exchanges and they are not shared across

vhosts for obvious reasons.

Custom Exchange Types

consistent-hash

The consistent hashing AMQP exchange type is a custom exchange type developed as a RabbitMQ plugin. It uses consistent hashing to route messages to queues. This helps distribute messages between queues more or less evenly.

A quote from the project README:

In various scenarios, you may wish to ensure that messages sent to an exchange are consistently and equally distributed across a number of different queues based on the routing key of the message. You could arrange for this to occur yourself by using a direct or topic exchange, binding queues to that exchange and then publishing messages to that exchange that match the various binding keys.

However, arranging things this way can be problematic:

It is difficult to ensure that all queues bound to the exchange will receive a (roughly) equal number of messages without baking in to the publishers quite a lot of knowledge about the number of queues and their bindings.

If the number of queues changes, it is not easy to ensure that the new topology still distributes messages between the different queues evenly.

Consistent Hashing is a hashing technique whereby each bucket appears at multiple points throughout the hash space, and the bucket selected is the nearest higher (or lower, it doesn't matter, provided it's consistent) bucket to the computed hash (and the hash space wraps around). The effect of this is that when a new bucket is added or an existing bucket removed, only a very few hashes change which bucket they are routed to.

In the case of Consistent Hashing as an exchange type, the hash is calculated from the hash of the routing key of each message received. Thus messages that have the same routing key will have the same hash computed, and thus will be routed to the same queue, assuming no bindings have changed.

x-random

The x-random AMQP exchange type is a custom exchange type developed as a RabbitMQ plugin by Jon Brisbin. A quote from the project README:

It is basically a direct exchange, with the exception that, instead of each consumer bound to that exchange with the same routing key getting a copy of the message, the exchange type randomly selects a queue to route to.

This plugin is licensed under Mozilla Public License 1.1, same as RabbitMQ.

Using the Publisher Confirms Extension

Please refer to RabbitMQ Extensions guide

Message Acknowledgements and Their Relationship to Transactions and Publisher Confirms

Consumer applications (applications that receive and process messages) may occasionally fail to process individual messages, or might just crash. Additionally, network issues might be experienced. This raises a question - "when should the RabbitMQ remove messages from queues?" This topic is covered in depth in the Queues guide, including prefetching and examples.

In this guide, we will only mention how message acknowledgements are related to AMQP transactions and the Publisher Confirms extension. Let us consider a publisher application (P) that communications with a consumer (C) using AMQP 0.9.1. Their communication can be graphically represented like this:

----- ----- ----- | | S1 | | S2 | | | P | ====> | B | ====> | C | | | | | | | ----- ----- -----

We have two network segments, S1 and S2. Each of them may fail. A publisher (P) is concerned with making sure that messages cross S1, while the broker (B) and consumer (C) are concerned with ensuring that messages cross S2 and are only removed from the queue when they are processed successfully.

Message acknowledgements cover reliable delivery over S2 as well as successful processing. For S1, P has to use transactions (a heavyweight solution) or the more lightweight Publisher Confirms, a RabbitMQ-specific extension.

Binding Queues to Exchanges

Queues are bound to exchanges using Bunny::Queue#bind. This topic is

described in detail in the Queues and Consumers

guide.

Unbinding Queues from Exchanges

Queues are unbound from exchanges using Bunny::Queue#unbind. This

topic is described in detail in the Queues and Consumers

guide.

Deleting Exchanges

Explicitly Deleting an Exchange

Exchanges are deleted using the Bunny::Exchange#delete:

x = ch.topic("groups.013c6a65a1de9b15658446c6570ec39ff615ba15")

x.delete

Auto-deleted exchanges

Exchanges can be auto-deleted. To declare an exchange as

auto-deleted, use the :auto_delete option on declaration:

ch.topic("groups.013c6a65a1de9b15658446c6570ec39ff615ba15", :auto_delete => true)

An auto-deleted exchange is removed when the last queue bound to it is unbound.

Exchange durability vs Message durability

See Durability guide

Wrapping Up

Publishers publish messages to exchanges. Messages are then routed to queues according to rules called bindings that applications define. There are 4 built-in exchange types in RabbitMQ and it is possible to create custom types.

Messages have a set of standard properties (e.g. type, content type) and can carry an arbitrary map of headers.

Most functions related to exchanges and publishing are found in two Bunny classes:

Bunny::ExchangeBunny::Channel

What to Read Next

The documentation is organized as a number of guides, covering various topics.

We recommend that you read the following guides first, if possible, in this order:

- Bindings

- RabbitMQ Extensions to AMQP 0.9.1

- Durability and Related Matters

- Error Handling and Recovery

- Concurrency Considerations

- Troubleshooting

- Using TLS (SSL) Connections

Tell Us What You Think!

Please take a moment to tell us what you think about this guide on Twitter or the Bunny mailing list

Let us know what was unclear or what has not been covered. Maybe you do not like the guide style or grammar or discover spelling mistakes. Reader feedback is key to making the documentation better.